So yesterday, we went to the Royal Opera House to see The Magic Flute. This didn’t strike me as something that would be relevant to gamedev – but hey, there are a few parallels!

The Magic Flute was Mozart’s final opera, opening just two months before his death in 1791. The operatic form was pretty mature by this point, having originated two centuries earlier in Italy, and Mozart himself had written 21 operas previously during his long career (the first, Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots, he wrote at the age of 11). Nevertheless, there’s a clear and playful fascination with the possibilities and limitations of the medium evident in the work.

The plot is set in motion by the Queen of the Night’s anguish and desire for revenge. Mozart wrote this part for his talented sister-in-law, Josepha Weber, who apparently possessed an exceptionally high range. The Queen of the Night’s second aria (video – lyrics), famously difficult, stretches the capabilities of the best sopranos. In the midst of exhorting her daughter to assassinate her enemy Sarastro, she bursts into a powerful, wordless high passage with the orchestra providing scant accompaniment (0:40 – 1:10 in the video above, and again at 1:55 – 2:17). Though emotive, these passages are clearly here to showcase the raw technical ability of the singer, free from such distractions as content.

Such exuberant virtuosity should feel familiar to any gamer. I’m put in mind of Gears of War, Epic’s technical tour de force from 2006. On several occasions, the game tugs the camera away from the action to check out a particularly impressive piece of architecture – sometimes with the player’s permission, sometimes forcibly. This moment happens about one minute after the opening tutorial and cinematic. There’s nothing subtle about Epic’s motives here: they have technical excellence and they want you to awe you with it.

There are a thousand such moments in a thousand games. Perhaps more memorable is the first sunrise in Crysis. After ten minutes of running through dense jungle at night the player crests a hill and is met with sunrise over an inviting tropical bay as orchestral music swells in the background. These technical moments of awe contribute to the mood, sure, but they’re very focused in their construction. They exist to demonstrate to the audience that they’re witnessing greatness, bringing admiration to the entire work both on this technical factor and on others via the halo effect.

Though each of these moments relies on introducing the contemporary audience to a previously unseen level of competency, this technique – the production laying raw skill bare before the audience – has been with us for hundreds of years or more. It doesn’t matter if it’s a complex guitar riff, an impossible breakdance move or a high F: the principles are the same.

But it’s not just bleeding-edge mainstream games that can be informed by the operatic tradition. The Magic Flute plays with its limitations as well as its possibilities.

Stagehands are the invisible angels of theatre. Most plays conceal the movement of props, dress their stagehands in black and change the scene in darkness if necessary and behind a curtain if possible. Not so here: in The Magic Flute, walls slide and descend mid-scene, performers hand off props to assistants between verses and characters are carried onto stage on the beds they are to lie on. Here, the people who change the set dress gaily, dance on and off and perform their jobs with a flourish. The composer trusts the audience to understand what is part of the work and what isn’t, transforms the ugly limitations of the medium into spectacle and eliminates a dozen stalling points in the process, allowing the production to career onwards at the pace which suits it best.

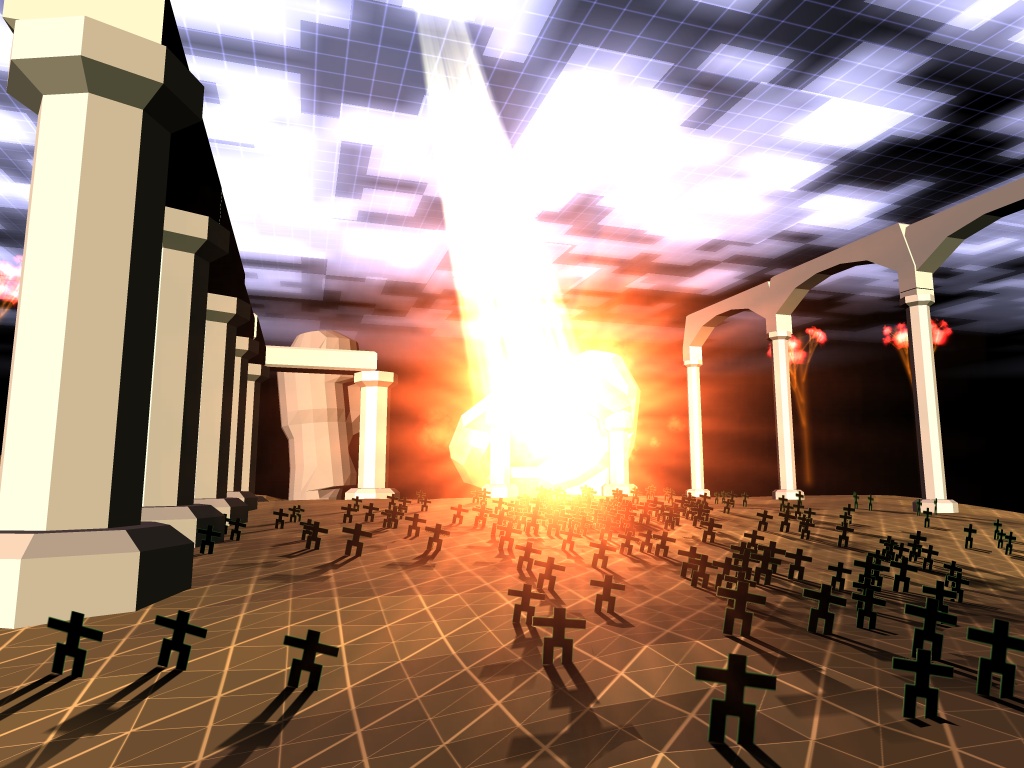

Flaunting your technical limitations and making them a strength requires that you be unashamed of them first, so it’s necessarily a newer trick in game development, but it’s been with us for at least as long as Gears of War – and from entirely the other end of the game development ecosystem.